- The lowest trophic level had food nutrients and are used by the organism more to fuel their activities and to build their body tissues.

- Mutualism- Bee & Flowers

Commensalism- Lizard & Spider

Predation- Mice & Snake

Parasitism- Tick & Carabao

Competition- Lion & Tiger - Balanced Ecosystem- there should be a balanced community of organism and their non living environment. Ecosystems are generally grouped into natural and man made ecosystem. In balanced ecosystem the process that normally take place in nature go on. Balance of nature is maintained. In general in a balance ecosystem the size of a particular prey population is affected by the number of the predators in the area, however this size of a particular predator population cannot increase beyond what each prey population can support.

Wednesday, July 20, 2011

Review: Page 37.

B.

Saturday, July 9, 2011

Monday, June 27, 2011

Limitation of Science

Mankind has never devised a better tool for solving the mysteries of the universe than science. However, there are some kinds of questions for which scientific problem solving is unsuited. In other words, science has limitations.

There are three primary areas for which science can't help us answer our questions. All of these have the same problem: The questions they present don't have testable answers. Since testability is so vital to the scientific process, these questions simply fall outside the venue of science.

The three areas of limitation are

Science can't answer questions about value. For example, there is no scientific answer to the questions, "Which of these flowers is prettier?" or "which smells worse, a skunk or a skunk cabbage?" And of course, there's the more obvious example, "Which is more valuable, one ounce of gold or one ounce of steel?" Our culture places value on the element gold, but if what you need is something to build a skyscraper with, gold, a very soft metal, is pretty useless. So there's no way to scientifically determine value.

Science can't answer questions of morality. The problem of deciding good and bad, right and wrong, is outside the determination of science. This is why expert scientific witnesses can never help us solve the dispute over abortion: all a scientist can tell you is what is going on as a fetus develops; the question of whether it is right or wrong to terminate those events is determined by cultural and social rules--in other words, morality. The science can't help here.

Note that I have not said that scientists are exempt from consideration of the moral issues surrounding what they do. Like all humans, they are accountable morally and ethically for what they do.

Finally, science can't help us with questions about the supernatural. The prefix "super" means "above." So supernatural means "above (or beyond) the natural." The toolbox of a scientist contains only the natural laws of the universe; supernatural questions are outside their reach.

In view of this final point, it's interesting how many scientists have forgotten their own limitations. Every few years, some scientist will publish a book claiming that he or she has either proven the existence of a god, or proven that no god exists. Of course, even if science could prove anything (which it can't), it certainly can't prove this, since by definition a god is a supernatural phenomenon.

So the next time someone invokes "scientific evidence" to support his or her point, sit back for a moment and consider whether they've stepped outside of these limitations.

There are three primary areas for which science can't help us answer our questions. All of these have the same problem: The questions they present don't have testable answers. Since testability is so vital to the scientific process, these questions simply fall outside the venue of science.

The three areas of limitation are

Science can't answer questions about value. For example, there is no scientific answer to the questions, "Which of these flowers is prettier?" or "which smells worse, a skunk or a skunk cabbage?" And of course, there's the more obvious example, "Which is more valuable, one ounce of gold or one ounce of steel?" Our culture places value on the element gold, but if what you need is something to build a skyscraper with, gold, a very soft metal, is pretty useless. So there's no way to scientifically determine value.

Science can't answer questions of morality. The problem of deciding good and bad, right and wrong, is outside the determination of science. This is why expert scientific witnesses can never help us solve the dispute over abortion: all a scientist can tell you is what is going on as a fetus develops; the question of whether it is right or wrong to terminate those events is determined by cultural and social rules--in other words, morality. The science can't help here.

Note that I have not said that scientists are exempt from consideration of the moral issues surrounding what they do. Like all humans, they are accountable morally and ethically for what they do.

Finally, science can't help us with questions about the supernatural. The prefix "super" means "above." So supernatural means "above (or beyond) the natural." The toolbox of a scientist contains only the natural laws of the universe; supernatural questions are outside their reach.

In view of this final point, it's interesting how many scientists have forgotten their own limitations. Every few years, some scientist will publish a book claiming that he or she has either proven the existence of a god, or proven that no god exists. Of course, even if science could prove anything (which it can't), it certainly can't prove this, since by definition a god is a supernatural phenomenon.

So the next time someone invokes "scientific evidence" to support his or her point, sit back for a moment and consider whether they've stepped outside of these limitations.

Saturday, June 25, 2011

Hypothesis about the over population of Janitor Fish

So, when you hear stories about how they are taking over Marikina River and Laguna de Bay and how hard it is to get rid of them, well, just think how that janitor fish survived. The janitor fish multiply so fast that, combined with their amazing ability for survival, and you have people complaining about how they are fast infesting our lakes. In a forum called Scientist Solutions, someone described the scenario this way: “If you throw a fishing net in one of our affected lakes, you can get a boatful (dinghy size) in about 5 minutes.”

Despite the assurance of that Auburn University fish curator that the janitor fish is edible, they have not found their way into our cuisine. However, some enterprising people have found some good use for them — as biofuel, the fish bones as water purifier, and fish skin as accent for footwear. The lowly janitor fish comes of age.

Hypothesis:

Because of the janitor fish that multiply so fast, combined with their amazing ability for survival and you have people complaining about how they are fast infesting our lakes. Among these invasive species in the "Pterygoplochthys pardalis found in marikina and Pterygoplochthys disjunctivus found in laguna de Bay.

Despite the assurance of that Auburn University fish curator that the janitor fish is edible, they have not found their way into our cuisine. However, some enterprising people have found some good use for them — as biofuel, the fish bones as water purifier, and fish skin as accent for footwear. The lowly janitor fish comes of age.

Hypothesis:

Because of the janitor fish that multiply so fast, combined with their amazing ability for survival and you have people complaining about how they are fast infesting our lakes. Among these invasive species in the "Pterygoplochthys pardalis found in marikina and Pterygoplochthys disjunctivus found in laguna de Bay.

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

BIOLOGY

Biology, the science of life. The term was introduced in Germany in 1800 and popularized by the French naturalist Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck as a means of encompassing the growing number of disciplines involved with the study of living forms. The unifying concept of biology received its greatest stimulus from the English zoologist Thomas Henry Huxley, who was also an important educator. Huxley insisted that the conventional segregation of zoology and botany was intellectually meaningless and that all living things should be studied in an integrated way. Huxley’s approach to the study of biology is even more cogent today, because scientists now realize that many lower organisms are neither plants nor animals (see Prokaryote; Protista). The limits of the science, however, have always been difficult to determine, and as the scope of biology has shifted over the years, its subject areas have been changed and reorganized. Today biology is subdivided into hierarchies based on the molecule, the cell, the organism, and the population.

Molecular biology, which spans biophysics and biochemistry, has made the most fundamental contributions to modern biology. Much is now known about the structure and action of nucleic acids and protein, the key molecules of all living matter. The discovery of the mechanism of heredity was a major breakthrough in modern science. Another important advance was in understanding how molecules conduct metabolism, that is, how they process the energy needed to sustain life.

Cellular biology is closely linked with molecular biology. To understand the functions of the cell—the basic structural unit of living matter—cell biologists study its components on the molecular level. Organismal biology, in turn, is related to cellular biology, because the life functions of multicellular organisms are governed by the activities and interactions of their cellular components. The study of organisms includes their growth and development (developmental biology) and how they function (physiology). Particularly important are investigations of the brain and nervous system (neurophysiology) and animal behavior (ethology).

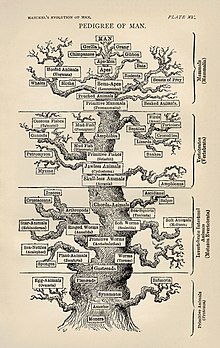

Population biology became firmly established as a major subdivision of biological studies in the 1970s. Central to this field is evolutionary biology, in which the contributions of Charles Darwin have been fully appreciated after a long period of neglect. Population genetics, the study of gene changes in populations, and ecology, the study of populations in their natural habitats, have been established subject areas since the 1930s. These two fields were combined in the 1960s to form a rapidly developing new discipline often called, simply, population biology. Closely associated is a new development in animal-behavior studies called sociobiology, which focuses on the genetic contribution to social interactions among animal populations.

Biology also includes the study of humans at the molecular, cellular, and organismal levels. If the focus of investigation is the application of biological knowledge to human health, the study is often termed biomedicine. Human populations are by convention not considered within the province of biology; instead, they are the subject of anthropology and the various social sciences. The boundaries and subdivisions of biology, however, are as fluid today as they have always been, and further shifts may be expected.

See Animal; Animal Behavior; Botany; Cell; Classification; Development; Ecology; Evolution; Genetics; Heredity; Life; Medicine; Metabolism; Plant; Reproduction; Respiration; Zoology.

Assignment:Scientific Method

1. Describe the Scientific Method.

Scientific method refers to a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge.To be termed scientific, a method of inquiry must be based on gathering empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of reasoning. TheOxford English Dictionary says that scientific method is: "a method of procedure that has characterized natural science since the 17th century, consisting in systematic observation, measurement, and experiment, and the formulation, testing, and modification of hypotheses.

2. What are the steps in a scientific method?

I. Observation. The scientific method starts with an observation of a natural occurrence.

II. Defining a Problem. As a result of one's initial observations, a question or problem may pose itself.

III. Formulation of a Hypothesis. Once the problem has been defined, the next step is to attempt to predict the answer based on one's observations.

IV.Experimentation. The hypothesis must be subjected to testing through experimentation.

V. Formulation of a Scientific Theory. Once the hypothesis is supported by scientific data, its status may be raised to that of a scientific theory.

Scientific method refers to a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge.To be termed scientific, a method of inquiry must be based on gathering empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of reasoning. TheOxford English Dictionary says that scientific method is: "a method of procedure that has characterized natural science since the 17th century, consisting in systematic observation, measurement, and experiment, and the formulation, testing, and modification of hypotheses.

2. What are the steps in a scientific method?

I. Observation. The scientific method starts with an observation of a natural occurrence.

II. Defining a Problem. As a result of one's initial observations, a question or problem may pose itself.

III. Formulation of a Hypothesis. Once the problem has been defined, the next step is to attempt to predict the answer based on one's observations.

IV.Experimentation. The hypothesis must be subjected to testing through experimentation.

V. Formulation of a Scientific Theory. Once the hypothesis is supported by scientific data, its status may be raised to that of a scientific theory.

Saturday, June 11, 2011

Assignment: History of Biology

The term biology in its modern sense appears to have been introduced independently by Karl Friedrich Burdach (1800), Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus(Biologie oder Philosophie der lebenden Natur, 1802), and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (Hydrogéologie, 1802). It is a classical compound inspired by theGreek word βίος, bios, "life" and the suffix -λογία, -logia, "study of."

Although biology in its modern form is a relatively recent development, sciences related to and included within it have been studied since ancient times.Natural philosophy was studied as early as the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indian subcontinent, and China. However, the origins of modern biology and its approach to the study of nature are most often traced back to ancient Greece. While the formal study of medicine dates back toHippocrates (ca. 460 BC – ca. 370 BC), it was Aristotle (384 BC – 322 BC) who contributed most extensively to the development of biology. Especially important are his History of Animals and other works where he showed naturalist leanings, and later more empirical works that focused on biological causation and the diversity of life. Aristotle's successor at the Lyceum, Theophrastus, wrote a series of books on botany that survived as the most important contribution of antiquity to the plant sciences, even into the Middle Ages.

Scholars of the medieval Islamic world who wrote on biology included al-Jahiz (781–869), Al-Dinawari (828–896), who wrote on botany,and Rhazes (865–925) who wrote on anatomy and physiology. Medicine was especially well studied by Islamic scholars working in Greek philosopher traditions, while natural history drew heavily on Aristotelian thought, especially in upholding a fixed hierarchy of life.

Biology began to quickly develop and grow with Antony van Leeuwenhoek's dramatic improvement of the microscope. It was then that scholars discoveredspermatozoa, bacteria, infusoria and the sheer strangeness and diversity of microscopic life. Investigations by Jan Swammerdam led to new interest inentomology and built the basic techniques of microscopic dissection and staining.

Advances in microscopy also had a profound impact on biological thinking itself. In the early 19th century, a number of biologists pointed to the central importance of the cell. In 1838 and 1839, Schleiden and Schwann began promoting the ideas that (1) the basic unit of organisms is the cell and (2) that individual cells have all the characteristics of life, although they opposed the idea that (3) all cells come from the division of other cells. Thanks to the work ofRobert Remak and Rudolf Virchow, however, by the 1860s most biologists accepted all three tenets of what came to be known as cell theory.

Meanwhile, taxonomy and classification became a focus in the study of natural history. Carolus Linnaeus published a basic taxonomy for the natural world in 1735 (variations of which have been in use ever since), and in the 1750s introduced scientific names for all his species. Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, treated species as artificial categories and living forms as malleable—even suggesting the possibility of common descent. Though he was opposed to evolution, Buffon is a key figure in the history of evolutionary thought; his work influenced the evolutionary theories of bothLamarck and Darwin.

Serious evolutionary thinking originated with the works of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck. However, it was the British naturalist Charles Darwin, combining the biogeographical approach of Humboldt, the uniformitarian geology of Lyell, Thomas Malthus's writings on population growth, and his own morphological expertise, that created a more successful evolutionary theory based on natural selection; similar reasoning and evidence led Alfred Russel Wallace to independently reach the same conclusions.

The discovery of the physical representation of heredity came along with evolutionary principles and population genetics. In the 1940s and early 1950s, experiments pointed to DNA as the component of chromosomes that held genes. A focus on new model organisms such as viruses and bacteria, along with the discovery of the double helical structure of DNA in 1953, marked the transition to the era of molecular genetics. From the 1950s to present times, biology has been vastly extended in the molecular domain. The genetic code was cracked by Har Gobind Khorana, Robert W. Holley andMarshall Warren Nirenberg after DNA was understood to contain codons. Finally, the Human Genome Project was launched in 1990 with the goal of mapping the general human genome. This project was essentially completed in 2003, with further analysis still being published. The Human Genome Project was the first step in a globalized effort to incorporate accumulated knowledge of biology into a functional, molecular definition of the human body and the bodies of other organisms.

Whats is Biology?

| BIOLOGY is a natural science concerned with the study of life and living things organisms, including their structure, function, growth, origin, evolution, distribution and taxonomy. It is a vast subject containing many subdivisions, topic and disciplines. |

- Bio -> Life

- Lobos -> Study

- Study of life

- Science of life

Why do we need to study biology? To know and understand ourselves and the world we live in.

Branches of Biology

- Aerobiology — the study of airborne organic particles

- Agriculture — the study of producing crops from the land, with an emphasis on practical applications

- Anatomy — the study of form and function, in plants, animals, and other organisms, or specifically in humans

- Astrobiology — the study of evolution, distribution, and future of life in the universe—also known as exobiology, exopaleontology, and bioastronomy

- Biochemistry — the study of the chemical reactions required for life to exist and function, usually a focus on the cellular level

- Bioengineering — the study of biology through the means of engineering with an emphasis on applied knowledge and especially related to biotechnology

- Bioinformatics — the use of information technology for the study, collection, and storage of genomic and other biological data

- Biomathematics or Mathematical Biology — the quantitative or mathematical study of biological processes, with an emphasis on modeling

- Biomechanics — often considered a branch of medicine, the study of the mechanics of living beings, with an emphasis on applied use through prosthetics or orthotics

- Biomedical research — the study of the human body in health and disease

- Biophysics — the study of biological processes through physics, by applying the theories and methods traditionally used in the physical sciences

- Biotechnology — a new and sometimes controversial branch of biology that studies the manipulation of living matter, including genetic modification and synthetic biology

- Building biology — the study of the indoor living environment

- Botany — the study of plants

- Cell biology — the study of the cell as a complete unit, and the molecular and chemical interactions that occur within a living cell

- Conservation Biology — the study of the preservation, protection, or restoration of the natural environment, natural ecosystems, vegetation, and wildlife

- Cryobiology — the study of the effects of lower than normally preferred temperatures on living beings.

- Developmental biology — the study of the processes through which an organism forms, from zygote to full structure

- Ecology — the study of the interactions of living organisms with one another and with the non-living elements of their environment

- Embryology — the study of the development of embryo (from fecundation to birth). See also topobiology.

- Entomology — the study of insects

- Environmental Biology — the study of the natural world, as a whole or in a particular area, especially as affected by human activity

- Epidemiology — a major component of public health research, studying factors affecting the health of populations

- Ethology — the study of animal behavior

- Evolutionary Biology — the study of the origin and descent of species over time

- Genetics — the study of genes and heredity

- Herpetology — the study of reptiles and amphibians

- Histology — the study of cells and tissues, a microscopic branch of anatomy

- Ichthyology — the study of fish

- Integrative biology — the study of whole organisms

- Limnology — the study of inland waters

- Mammalogy — the study of mammals

- Marine Biology — the study of ocean ecosystems, plants, animals, and other living beings

- Microbiology — the study of microscopic organisms (microorganisms) and their interactions with other living things

- Molecular Biology — the study of biology and biological functions at the molecular level, some cross over with biochemistry

- Mycology — the study of fungi

- Neurobiology — the study of the nervous system, including anatomy, physiology and pathology

- Oceanography — the study of the ocean, including ocean life, environment, geography, weather, and other aspects influencing the ocean

- Oncology — the study of cancer processes, including virus or mutation oncogenesis, angiogenesis and tissues remoldings

- Ornithology — the study of birds

- Population biology — the study of groups of conspecific organisms, including

- Population ecology — the study of how population dynamics and extinction

- Population genetics — the study of changes in gene frequencies in populations of organisms

- Paleontology — the study of fossils and sometimes geographic evidence of prehistoric life

- Pathobiology or pathology — the study of diseases, and the causes, processes, nature, and development of disease

- Parasitology — the study of parasites and parasitism

- Pharmacology — the study and practical application of preparation, use, and effects of drugs and synthetic medicines

- Physiology — the study of the functioning of living organisms and the organs and parts of living organisms

- Phytopathology — the study of plant diseases (also called Plant Pathology)

- Psychobiology — the study of the biological bases of psychology

- Sociobiology — the study of the biological bases of sociology

- Structural biology — a branch of molecular biology, biochemistry, and biophysics concerned with the molecular structure of biological macromolecules

- Virology — the study of viruses and some other virus-like agents

- Zoology — the study of animals, including classification, physiology, development, and behavior (See also Entomology, Ethology, Herpetology, Ichthyology, Mammalogy, and Ornithology)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)